|

0 Comments

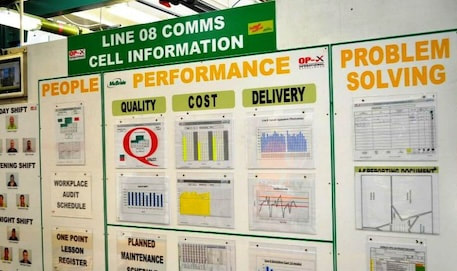

How can we break free from falling into the trap of silo departments working against each other, and empower staff to work together in a seamless, error free, flow of work that adapts to rapid changing circumstances? Here we are going to learn from ‘the liberated method’ and ‘self managed’ teams.

Designing complex systemic person centred services fail unless we use strength based approaches like the liberated method

The way we manage today calls on us to be more focused on our people, respond quicker to business problems, and deal with an increasing number of different type of issues.

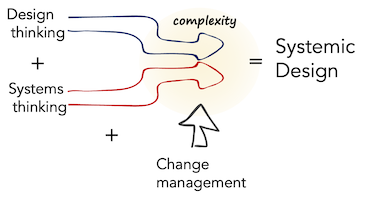

Complex person-centred public services and digital have to be designed in ways that are fundamentally different, to how we design transactional services.

Moving service design forwards into systemic design to incorporate systems thinking, allows us to expand the depth of how we can evolve organisations and design for complexity

Local government response to COVID-19 is giving us a glimpse of a new way of delivering our public services. What can we learn from this, and make Working Smarter the new way of working?

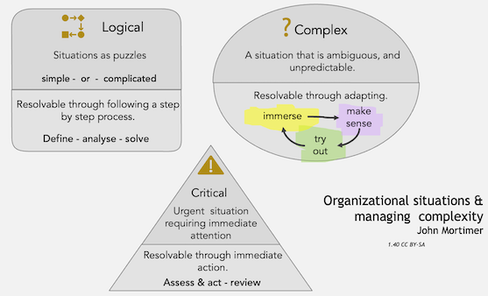

The context used to be we were designing things within systems that were relatively stable. Now we're designing things when the systems themselves need designing.

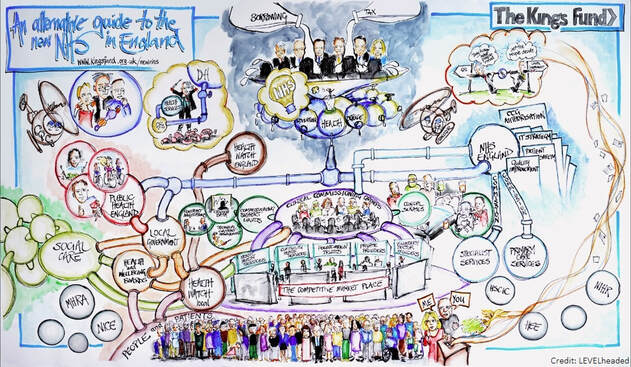

Understanding complexity and then applying that to dealing with people is critical to true service and systems design in our health services and ICS.

Data sharing, often a major stumbling block to joined-up working in the public sector. How to use a systemic approach to thinking about the problem and delivering a different and far easier solution.

Standardisation and centralisation in the public sector - another example of the unintended outcomes

Value and failure demand analysis. Using it will help you to see why certain issues remain resistant to change, regardless of how many consultants, or how much money is thrown at it.

Commissioning and outsourcing has failed in the public sector, new ways of understanding commissioning are taking hold in the UNDP and in many third sector organisations.

|