Housing & supporting people -strength based liberated method

Housing Allocations CBL and the impact of a strengths based systems thinking approach in a complex service

Allocating housing to citizens in need is often understood as a transactional service. However, when liberating the method staff use, we can then design housing using radical systemic design, and a far more effective strength based way of dealing with people in need emerges.

What is the context?

In England, as in most countries, local government councils are responsible to allocate housing to those members of the public who are in need of housing. Around 2002 an approach that was copied from The Netherlands, was brought over to England, and tested. It was brought in because the old system of allocating housing was different in each area, and decisions made were not transparent. There was also a feeling that the person in need should have the choice as to the location and type of house they could have.

The government at the time liked it, and they called it Choice Based Lettings (CBL). This system is still in place for 95% of all local government areas.

The government at the time liked it, and they called it Choice Based Lettings (CBL). This system is still in place for 95% of all local government areas.

What’s the story?

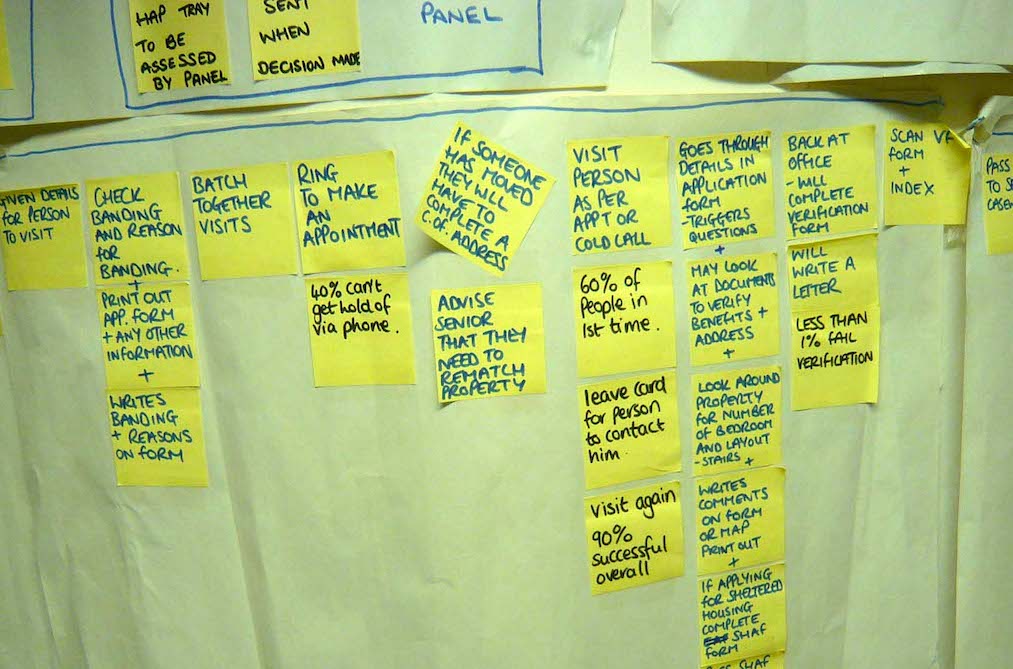

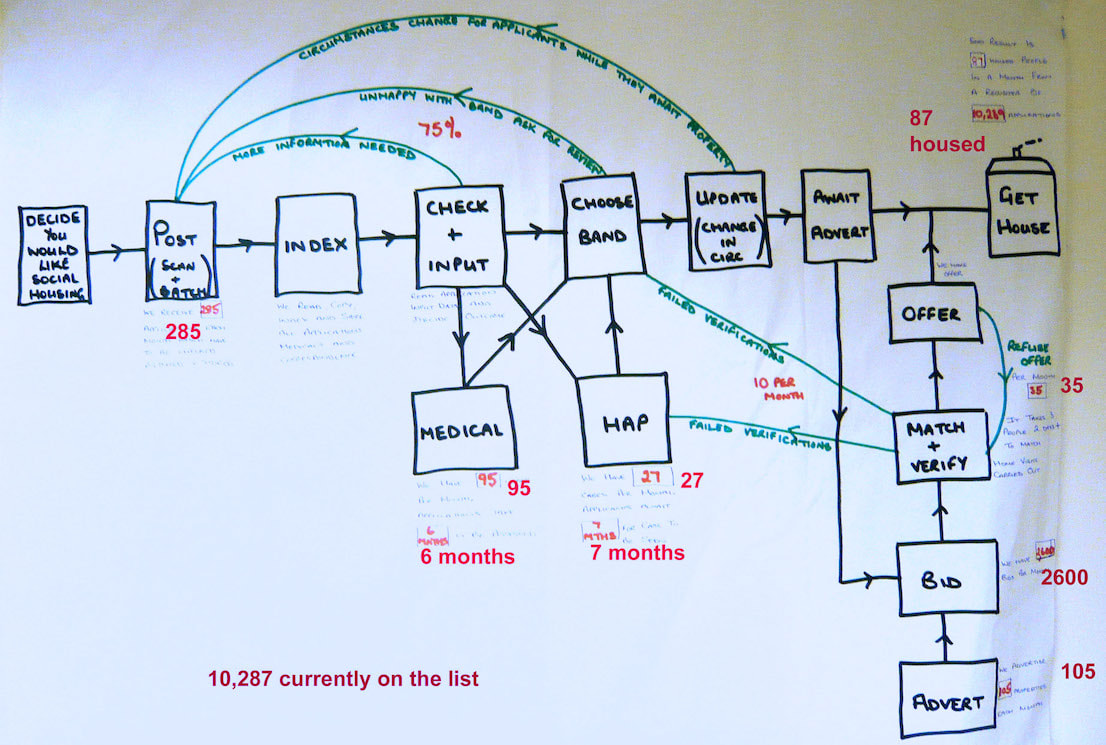

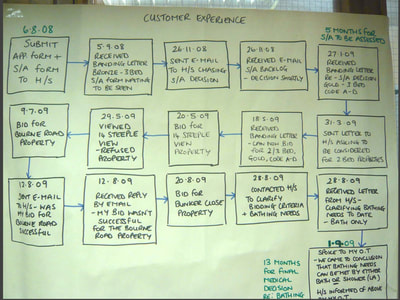

The manager and a team of front line staff got together to look at understanding the workflow as experienced buy the service users.

Looking at the start of the workflow, after the initial contact from service users, the majority of further contact was by letter. Just to get past the front door to be accepted took months. Each application generated huge efforts of logging, processing and filing across the three IT systems.

Kim Tugwell, Home Select Case Worker, said that spending all day ‘processing application forms’ felt like being ‘on a treadmill never getting anywhere’. The system also generated hostility and almost 10% of applicants appealed against their banding. For the team, the deeper learning then followed quickly after.

Looking at the start of the workflow, after the initial contact from service users, the majority of further contact was by letter. Just to get past the front door to be accepted took months. Each application generated huge efforts of logging, processing and filing across the three IT systems.

Kim Tugwell, Home Select Case Worker, said that spending all day ‘processing application forms’ felt like being ‘on a treadmill never getting anywhere’. The system also generated hostility and almost 10% of applicants appealed against their banding. For the team, the deeper learning then followed quickly after.

|

Audio - thoughts from the team about their service

|

The folly of banding

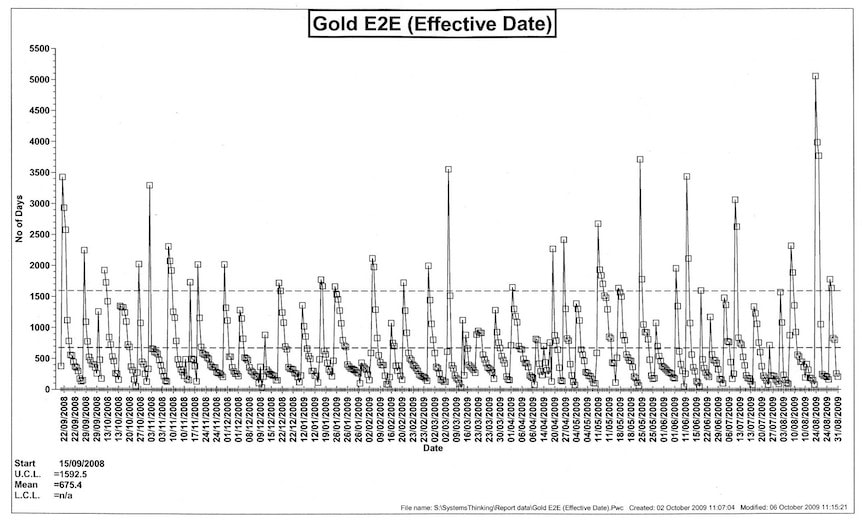

Banding is the term that means the groups that customers were put into once they had been assessed. There were three categories; gold, silver and bronze. The first shock and major learning point was that the Gold priority banding did not mean that you would be housed any quicker. It took on average up to 30 months to be housed.

Gold band mean = 675 days, Silver band mean = 750 days, Bronze band mean = 655 days.

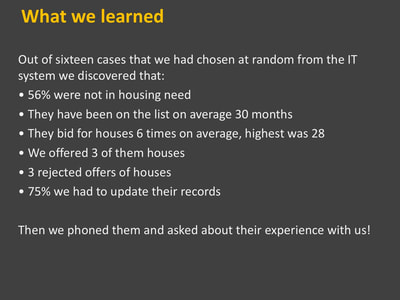

Housing need

The next thing that astonished the team was when they began to speak to people on the waiting list. Many of them were not actually in real housing need (56%); they could be removed from the list. Two thirds of all people that were contacted, had out of date records.

More learning came when the team began to understand the amount of activity that the CBL process generated. For example, of the 105 properties advertised 2,600 bids were received.

Housing need

The next thing that astonished the team was when they began to speak to people on the waiting list. Many of them were not actually in real housing need (56%); they could be removed from the list. Two thirds of all people that were contacted, had out of date records.

More learning came when the team began to understand the amount of activity that the CBL process generated. For example, of the 105 properties advertised 2,600 bids were received.

It became clear CBL users had little choice or control, just the illusion of control...

Understanding strength based real need

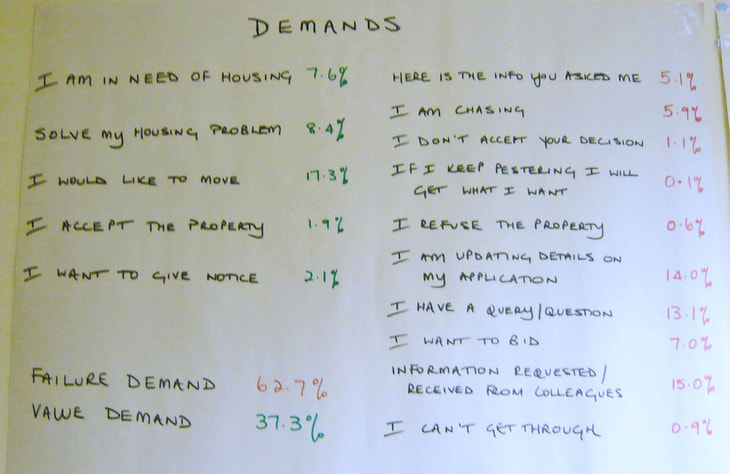

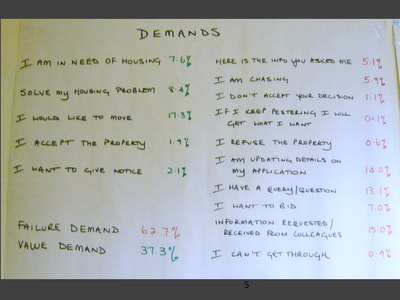

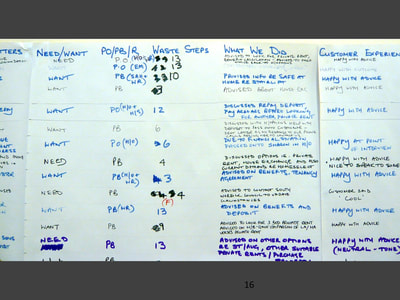

We started off with looking at demands, and understanding what really mattered to citizens.

We then summarised a months demands into one sheet and split them into Value & Failure demands. The failure demands are those that are caused by the way we have designed the service itself. Therefore, we have the potential, when we redesign the service, to eliminate the failure demands.

We then summarised a months demands into one sheet and split them into Value & Failure demands. The failure demands are those that are caused by the way we have designed the service itself. Therefore, we have the potential, when we redesign the service, to eliminate the failure demands.

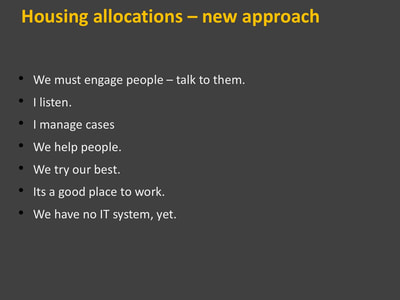

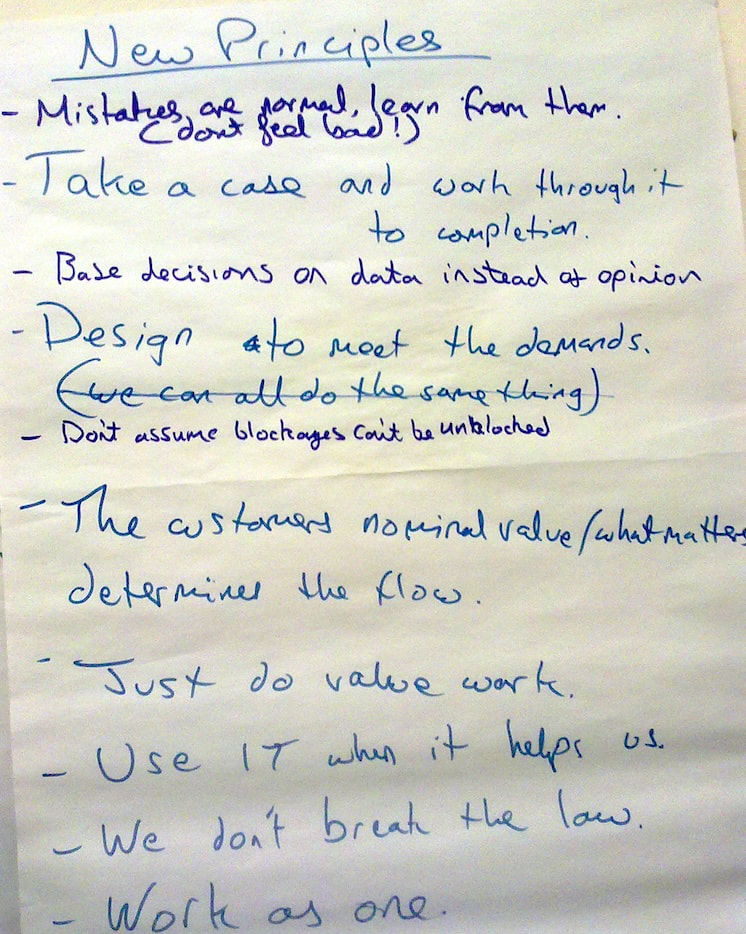

The experiment - liberated method principles

An important part of the intervention design methodology, is a safe to try environment. The team were given a physical room, so they could be disconnected with the current mindset, procedures, culture and ways of working of the current organisation. I call this 'the bubble' which is an innovation method that is designed to allow for people to truly come up with new ways of working unencumbered by the current systemic conditions. The team are led to work as a design team, across their specialisms, on the end to end service, to focus on learning by taking customer demands directly into the team.

The team were given permission to liberate their working principles to experiment with new ways of working.

The liberated method principles based on working in local government with people who need us:

- Understand what matters for each person, this determines the design.

- We make decisions based on knowledge and evidence, not opinion or standards.

- Only do what is needed to create value, enabling the person to gain control.

- Take ownership through the end to end journey with the person.

- Work as a team, without department barriers.

- We are here to learn, and improve.

Rule 1 - do not break the law.

Rule 2 - do not make their situation worse.

The next discovery emerged gradually. It is a lesson about closely understanding demand. One housing applicant (Mary) made contact during the trial. Mary wanted to move to a one-bedroom bungalow. Her application form included a medical form guaranteeing a higher banding. This would have secured Mary a silver band classification and allowed her to bid online. One-bedroom bungalows are rare and there were very few in her chosen location. So, she would never be housed adequately and she will remain on the list in the expectation that a house may become available.

The team were given permission to liberate their working principles to experiment with new ways of working.

The liberated method principles based on working in local government with people who need us:

- Understand what matters for each person, this determines the design.

- We make decisions based on knowledge and evidence, not opinion or standards.

- Only do what is needed to create value, enabling the person to gain control.

- Take ownership through the end to end journey with the person.

- Work as a team, without department barriers.

- We are here to learn, and improve.

Rule 1 - do not break the law.

Rule 2 - do not make their situation worse.

The next discovery emerged gradually. It is a lesson about closely understanding demand. One housing applicant (Mary) made contact during the trial. Mary wanted to move to a one-bedroom bungalow. Her application form included a medical form guaranteeing a higher banding. This would have secured Mary a silver band classification and allowed her to bid online. One-bedroom bungalows are rare and there were very few in her chosen location. So, she would never be housed adequately and she will remain on the list in the expectation that a house may become available.

So conditioned were the team, that it took a great deal of debate and three phone calls to truly understand what mattered about how a service could best be delivered to Mary. As the team asked her more questions, they learnt that Mary actually loved the house she was living in, but could not afford a gardener to maintain the garden. Her mobility was gradually being reduced over time. Her real need was help with her garden and to stay in her home, so the team arranged for a voluntary group to do the gardening for her, allowing her to continue to live in the same property, where she was happy. We had started learning about a strength based approach!

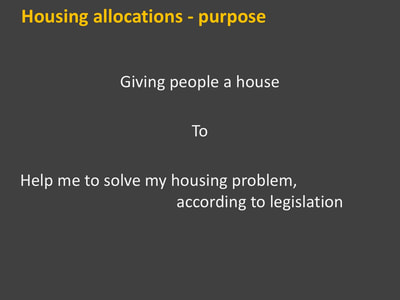

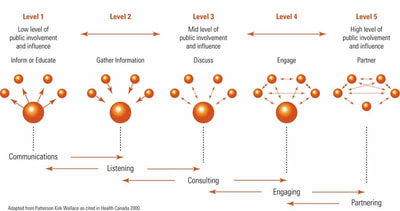

Solving people’s problems & liberate staff to embrace a flexible strength based approach

The assumption in the workflow design was that everybody who made contact did so because they wanted a house, making the assumed purpose of the service ‘I want a house’. When the team began to listen carefully and ask questions,

what they found was that many people who made contact were actually suitably housed but needed a different housing related problem solved.

The application form and the system design ensured that people making contact never really got to speak to a human being. All demand (100%) got translated into ‘give me a house’. In reality only 15% of that demand had a high housing need. High housing need of itself does not mean that that the solution should be social housing. Often people asking for help only wanted assistance with a deposit, so that they could move into private accommodation, or needed help to solve a dispute involving a private landlord. There are a huge range of solutions that can be tailored to solve each particular problem.

The real demand into the system might even suggest that the housing crisis that we are warned of is perhaps not as bad as it might seem. This knowledge is only possible because staff were free to have conversations and understand what the real problems were and what mattered to service users - a strength based focus. Gone are the application forms and the multiple and expensive IT systems that prevented officers from listening and understanding.

Great Yarmouth ended the Choice Based Lettings scheme that drove so much failure and cost into the system, and that stopped them from helping the people that they were there to serve. This then freed staff to both understand and then become creative in strength based helping people resolve that problem releases huge energy and creativity. It turns staff from paper shufflers back into human beings. Only people, not IT, has the ability to absorb the huge range of demand that is presented in human service systems.

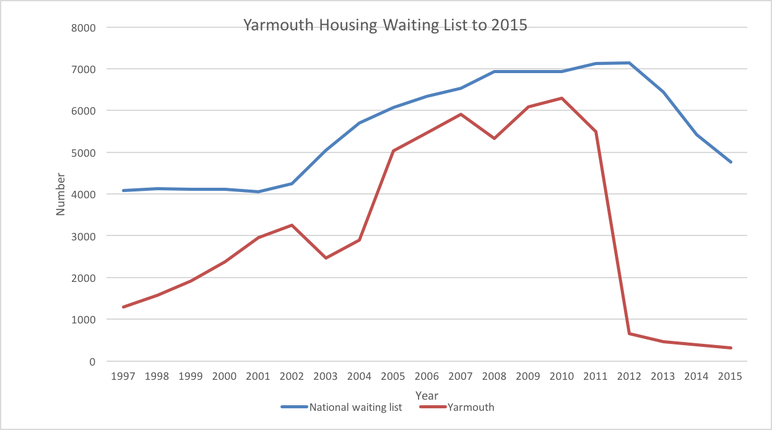

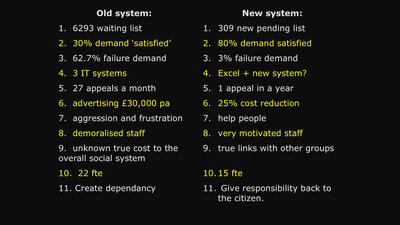

Over time, the waiting list dropped from 6000 in 2010 to 309 in 2015. The Home Select team have a new strength based purpose now expressed in customer terms: ‘help me solve my housing problem’.

what they found was that many people who made contact were actually suitably housed but needed a different housing related problem solved.

The application form and the system design ensured that people making contact never really got to speak to a human being. All demand (100%) got translated into ‘give me a house’. In reality only 15% of that demand had a high housing need. High housing need of itself does not mean that that the solution should be social housing. Often people asking for help only wanted assistance with a deposit, so that they could move into private accommodation, or needed help to solve a dispute involving a private landlord. There are a huge range of solutions that can be tailored to solve each particular problem.

The real demand into the system might even suggest that the housing crisis that we are warned of is perhaps not as bad as it might seem. This knowledge is only possible because staff were free to have conversations and understand what the real problems were and what mattered to service users - a strength based focus. Gone are the application forms and the multiple and expensive IT systems that prevented officers from listening and understanding.

Great Yarmouth ended the Choice Based Lettings scheme that drove so much failure and cost into the system, and that stopped them from helping the people that they were there to serve. This then freed staff to both understand and then become creative in strength based helping people resolve that problem releases huge energy and creativity. It turns staff from paper shufflers back into human beings. Only people, not IT, has the ability to absorb the huge range of demand that is presented in human service systems.

Over time, the waiting list dropped from 6000 in 2010 to 309 in 2015. The Home Select team have a new strength based purpose now expressed in customer terms: ‘help me solve my housing problem’.

Home Select Manager said that the job is now much more satisfying as it is about ‘getting out there, building relationships and understanding people’.

What has been the impact?

Housing allocations and homelessness, financial advice, benefits advice, social care, anti-social behaviour, the third sector, and the community. They are all now a part of housing allocations in the minds of the officers. This enables them to come up with a new strength based way of thinking about their job. The outcomes after moving this work in a fully developed service are below.

|

Old system

6293 waiting list 30% demand ‘satisfied’ 62.7% failure demand 3 IT systems 27 appeals a month advertising £30,000 pa aggression and frustration demoralised staff unknown true cost to the overall social system 22 FTE fire-fighting manager |

New system

309 new list 80% problems resolved 3% failure demand 1 simple IT system 1 appeal in a year 25% cost reduction helping people, encourage independence staff seeking to improve true links with other groups 15 FTE In control and fixing systemic barriers |

The graph below shows the red line drop in the waiting list in Yarmouth over the next two years. Elements of the new approach were published by central government in one of their guidance documents, resulting in the reduction of national waiting lists - the blue line.

Audio - Reflections from the team

|

The new service, and what it is like now.

|

What have been the key elements of success?

- The manager and the staff viewing their current work from the service users perspective.

- Designing a system that liberates staff to deal with the variety of what was presented.

- Listen and understand each service users real needs and what matters to them - focusing on a strength based approach rather than a deficiency focus.

- Actively transforming the workflow with systemic approach, challenging and removing waste.

- The increase in real outcomes improved people’s lives, and impacts the public sector as a whole.

- Decision-making is delegated to staff, liberating them to apply the appropriate methods.

- The emergence of motivation and enthusiasm of staff.

What has been learned?

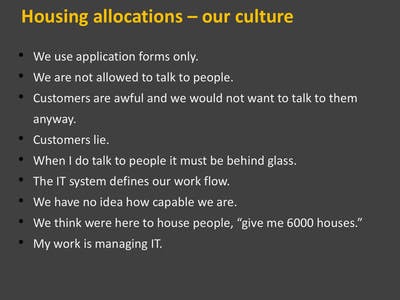

The big finding about this is that the service had been inadvertently designed to ration properties and make people go through difficult steps in order to prove how in need they were. This was to protect the system from a public who would be devious enough to exaggerate their need to get a property. It was an inside-out deficiency focused design.

The application form was the perfect embodiment of this thinking: a long document that asked questions designed to sift out lies, with little or no relevance to the real problems that people needed help with. In fact the application form acted like a very basic front-end, unresponsive and bureaucratic. One real surprise the team learned was that people told the truth and they generally wanted help to solve a problem if they are given the chance to express their real needs.

The strength based logic that follows that realisation leads to a dramatic re-orientation of the mind-set of the staff, and most importantly the managers. The team realised that the application form could not be a reliable method for understanding people’s real problems or strengths. Only human beings can deal with the variety of demand presented by people.

The application form was the perfect embodiment of this thinking: a long document that asked questions designed to sift out lies, with little or no relevance to the real problems that people needed help with. In fact the application form acted like a very basic front-end, unresponsive and bureaucratic. One real surprise the team learned was that people told the truth and they generally wanted help to solve a problem if they are given the chance to express their real needs.

The strength based logic that follows that realisation leads to a dramatic re-orientation of the mind-set of the staff, and most importantly the managers. The team realised that the application form could not be a reliable method for understanding people’s real problems or strengths. Only human beings can deal with the variety of demand presented by people.

- A standard approach to workflow design, leads to poor outcomes, creates waste and increases demand.

- Systemic design thinking principles of user centric services does reduce demand and resources, and increase the value for the customer.

- Real transformation is about altering how we think about delivering services, the courage to fundamentally design the workflow, how well we can remove organisational barriers, and liberating staff to deal with problems.

- Transferring power away from the organisation, to the person in need, creates fundamentally different behaviours. And people begin to take control of aspects of their lives and the strengths around them.

Our beliefs drive our design

It is important to realise that the core of this work is about the way we think about our service, and how that impact the design. This was also about looking at systemic change. These shifted for this transformation to occur.

|

Assumed truths

we have to manage a huge waiting list the private sector housing is not suitable for us we can only make a difference to very few people IT can really help us we have to tell people what they can have we must treat everyone the same we design a transactional service to manage demand |

Learned truths

the large waiting list is an outcome of a broken system if we work with landlords, they can provide suitable housing everyone can be helped who need it digital front ends a barriers we help people take responsibility for their own lives through their strengths deal with people according to them as individual people designing around complexity is very different |

Implications for other Local Government

Transformation like this case study is not recommended for every organisation. Each council or housing provider can examine its own services – and their impact on those in need, then decide themselves how far they want to go in re-designing their services. In Yarmouths’ case, they decided to focus on a strengths based approach, to change every part of the service and remove CBL.

Articles from this Case Study

How Norfolk council has cut its waiting list, The Guardian 10 April 2018

Published in Inside Housing 2011,

Published by Vanguard Consulting 2012

Input to CLG guidance document 2012.

Client manager: Mark Burns, consultant: John Mortimer - Vanguard Consulting

Published in Inside Housing 2011,

Published by Vanguard Consulting 2012

Input to CLG guidance document 2012.

Client manager: Mark Burns, consultant: John Mortimer - Vanguard Consulting